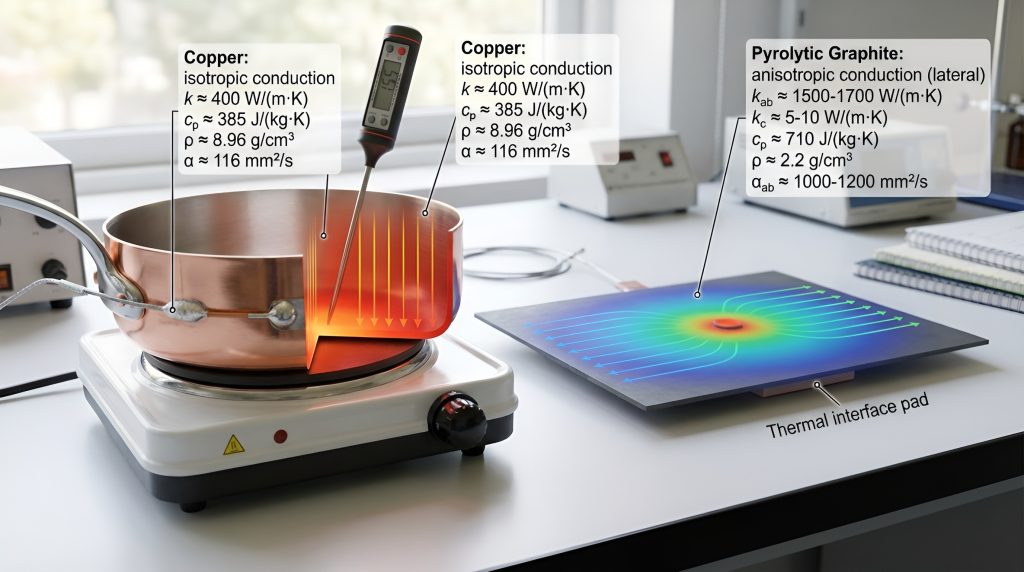

When comparing graphite vs. copper cores, the question of which has a faster heat response depends entirely on the direction of heat flow and the specific thermal properties required for your application. Copper is an industry standard known for its high thermal conductivity (approximately 400 W/m·K) and isotropic nature, meaning it moves heat equally well in all directions. This makes copper cores the premier choice for high-performance cookware and heavy-duty electronics where heat must move quickly through the thickness of the material. However, modern engineering has introduced pyrolytic graphite, which boasts a significantly higher in-plane conductivity (up to 1500 W/m·K) while remaining incredibly lightweight. If your goal is rapid lateral spreading to eliminate hotspots in slim devices like smartphones or laptops, graphite often outperforms copper due to its superior thermal diffusivity.

Understanding the trade-offs between these two materials is essential for optimizing energy efficiency, safety, and performance. While copper offers a predictable and robust response for transferring heat across layers, graphite’s anisotropy—its tendency to conduct heat much faster across its surface than through its depth—requires a more strategic design approach. Choosing the right core involves weighing factors like thermal mass, contact resistance, and the specific geometry of your system. Whether you are a professional chef seeking the perfect sear or a hardware engineer managing CPU thermals, this guide provides a quantitative comparison of copper and graphite to help you determine which material offers the fastest, most effective heat response for your needs.

Why Heat Response Matters: Graphite vs. Copper Core

You’ll get a focused, comparative view of how graphite and copper cores behave when heat is applied. Understanding heat response — how quickly a material changes temperature and spreads heat — helps you judge performance, safety, and energy efficiency in cookware, electronics, and thermal systems.

This article covers basic thermal physics, a quantitative comparison of properties, the effects of construction and interfaces, trusted test methods, application outcomes, and a practical decision framework so you can choose the right core for your specific needs. It gives clear, actionable guidance with quantified trade-offs included.

Understanding Thermal Conductivity, Heat Capacity, and Diffusivity

The three properties you must track

You need to think in terms of three physical properties, because together they determine how quickly a material’s temperature changes and how fast heat moves through it.

These combine into thermal diffusivity, α = k / (ρ·cp), which directly controls the speed at which a temperature change propagates through a material. If α is large, a surface temperature step diffuses quickly into (or across) the material.

Why conductivity and thermal mass act differently

High k makes heat flow quickly across the material, which you feel as rapid lateral equalization (good for cookware bottoms or heat spreaders). Low ρ·cp reduces the total thermal mass that must be heated, so surface temperature rises faster for a given heat input. Practically, copper has very high k (~400 W/m·K) but also high ρ; graphite/carbon can have lower bulk k but much lower density and a higher cp, so the net α can be similar in some orientations.

Example product context:

Anisotropy and contact resistance — the real-world spoilers

Graphite is often highly anisotropic: its in-plane conductivity can be tens to hundreds of times greater than through-thickness conductivity. That makes it excellent for spreading heat laterally but poor at moving heat across a thickness. Copper is effectively isotropic, so its behavior is more predictable.

Contact resistance at interfaces (poor surface flatness, gaps, oxides) can dominate performance. To reduce it you should:

Quick, actionable checks

Material Properties: Quantitative Comparison of Copper and Graphite

Representative physical values you can use

You’ll get faster intuition if you work with numbers. Typical, representative properties (order-of-magnitude, engineering values) are:

These ranges explain why graphite can sometimes “beat” copper in spreading but lose badly when you need heat to cross thickness.

How to compute thermal diffusivity (and why it matters)

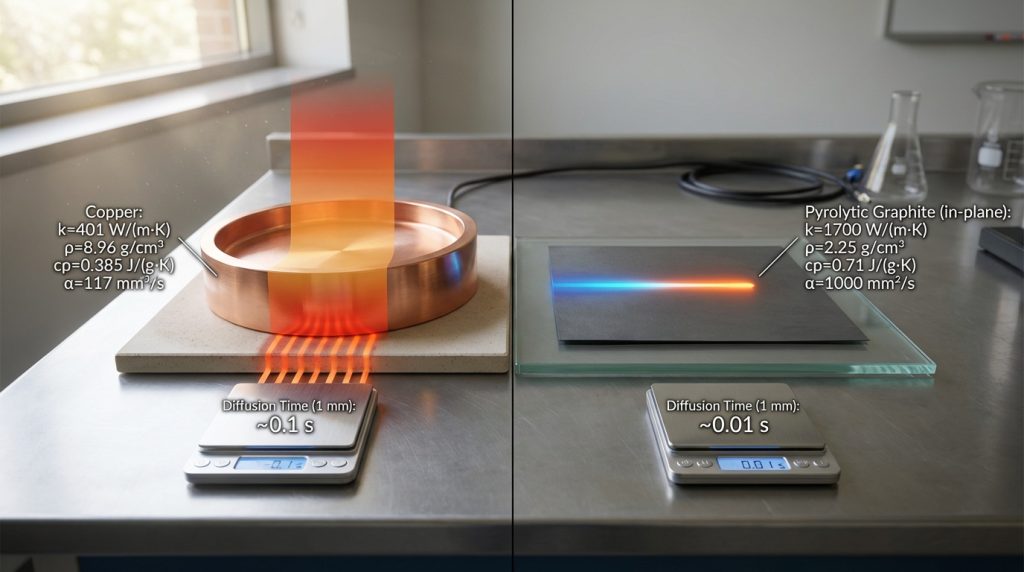

Thermal diffusivity α = k / (ρ·cp) controls how fast a temperature perturbation spreads through material. Workable examples:

Practical rule: diffusion time scales like t ≈ L²/α. For a 1 mm path (L = 0.001 m):

So, in-plane graphite can diffuse lateral temperature changes an order of magnitude faster than copper for the same path length; graphite’s through-thickness response can be orders of magnitude slower.

Thermal effusivity — the “how it feels” metric

Effusivity e = sqrt(k·ρ·cp) measures how readily a material exchanges heat with another body (how “hot” a surface feels under a heat pulse). Using the representative numbers:

Surprisingly, copper and highly ordered graphite can have similar effusivity, so an initial surface temperature jump can feel comparable even though the internal diffusion mechanisms differ.

Practical takeaways and product context

Next, you’ll see how core construction, geometry, and interfaces amplify or negate these material advantages in real assemblies.

How Core Construction, Geometry and Interfaces Change Heat Response

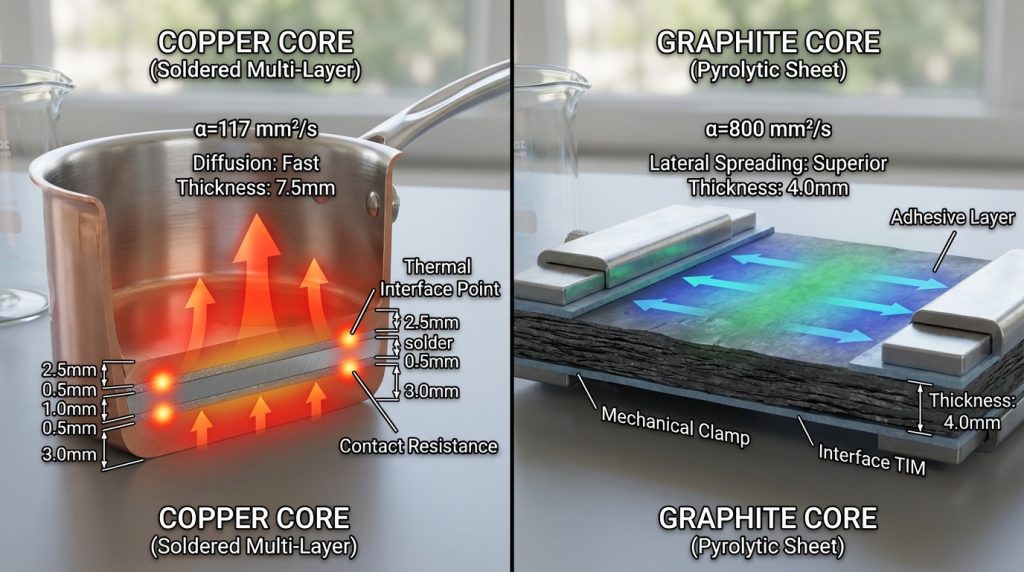

You’ve seen raw material numbers — now learn why a part’s construction often determines the real-world heat response. Small changes in thickness, layering, surface area and interfaces can flip who “wins” in a product.

Heat spreading vs. through-thickness transfer

Heat has two jobs: move laterally (spread) and move through thickness (transfer). Thin copper layers heat locally very fast because of high k and small thermal mass; they give rapid local temperature rise but limited lateral reach. Conversely, a thicker graphite spreader (high in-plane k) will equalize temperature across a surface faster — think laptop graphite sheets (Apple, Samsung) that take hotspots and smear them out.

Tip: if your failure mode is a hotspot (local power spike), prioritize in-plane spreading; if you must transfer heat across a thickness (cookware, heat pipes, vias), prioritize through-thickness α.

Geometry, thickness and surface area

Time constant scales like t ≈ L²/α. Doubling core thickness quadruples diffusion time. Adding fins or increasing surface area improves convective cooling but does nothing to intrinsic in-plane vs through-thickness tradeoffs.

Actionable step: for faster response, reduce the critical thermal path L (thin the layer), or increase α (choose higher-diffusivity material) in that direction.

Interfaces: bonding layers, TIMs and contact resistance

Interfaces often dominate. An adhesive layer, oxide film or an air gap can add orders of magnitude more resistance than the bulk. Examples:

Practical tip: eliminate air gaps, use properly applied TIM (thin, well-wetted), and prefer metallurgical bonds where reliability is critical.

Failure modes that slow and kill response

Quick product notes: All-Clad Copper Core pans heat quickly and keep good through-thickness transfer because the copper is clamped and bonded; Thermal Grizzly Carbonaut / Fujipoly graphite pads excel as thin lateral spreaders but need flat surfaces and correct orientation.

Next, you’ll learn how to measure these behaviors reliably — what tests and metrics cut through marketing claims.

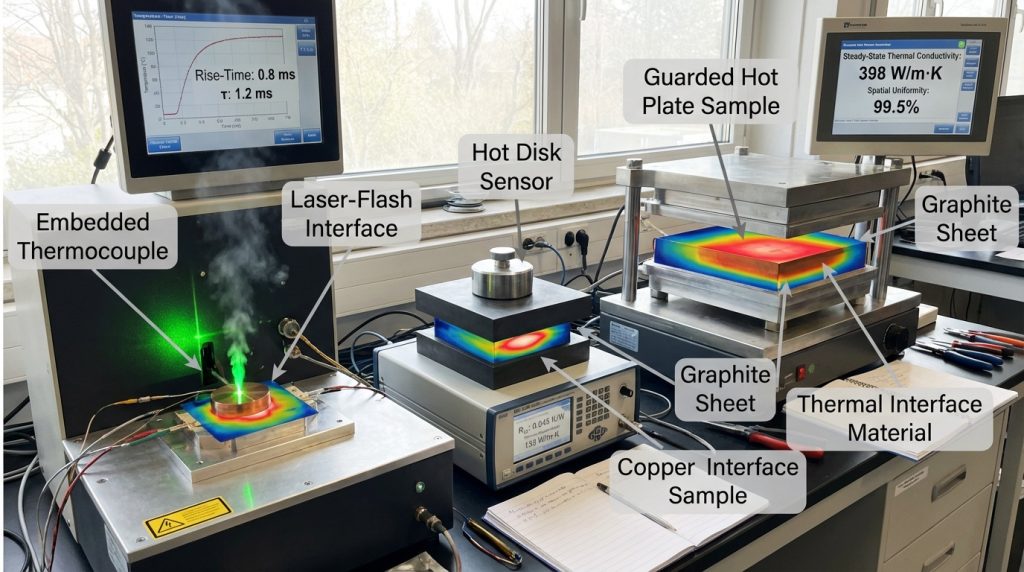

How Heat Response Is Measured: Tests, Protocols, and Metrics You Should Trust

You’ll be guided through standard and practical measurement methods so you can interpret claims and run meaningful tests yourself. Below are the transient and steady-state lab techniques, application-focused tests, the metrics that matter, and the common pitfalls to avoid.

Transient techniques (diffusivity and short-time behavior)

Transient methods capture how quickly heat begins to move through a material.

How you use them: prepare flat, well-polished samples, control sample thickness, and run multiple shots to check repeatability.

Steady-state methods (thermal conductivity)

Steady-state tests measure k under constant heat flow.

Application-oriented tests (real-world relevance)

These show operational performance you’ll feel or measure in the field.

Key metrics to trust

Common pitfalls & best practices

Practical tip: if a vendor only quotes bulk k without specifying direction, thickness, or interface treatment, treat the number as incomplete — ask for test method, sample geometry and uncertainty.

Application-Level Performance: Cookware, Electronics, and Thermal Management Systems

You’ll find an application-focused comparison that translates material physics into practical outcomes. Below are clear, real-world takeaways so you can pick and specify the right core for your product or purchase.

Cookware: surface response, evenness, and retained heat

In the kitchen, you care about how fast a pan responds, how evenly it cooks, and how well it retains heat when ingredients are added.

Practical tips:

Electronics and heat spreaders: spot cooling vs. area spreading

Your electronic hotspots are small and intense; your design constraints are weight and space.

How to choose:

High-power sinks, battery modules, and hybrid strategies

At high power, you’ll juggle thermal resistance, mass, manufacturability, and mechanical needs.

Hybrid approaches you can implement:

Actionable checklist:

Next, you’ll use these application insights to build a practical decision framework for selecting the right core for your specific use case.

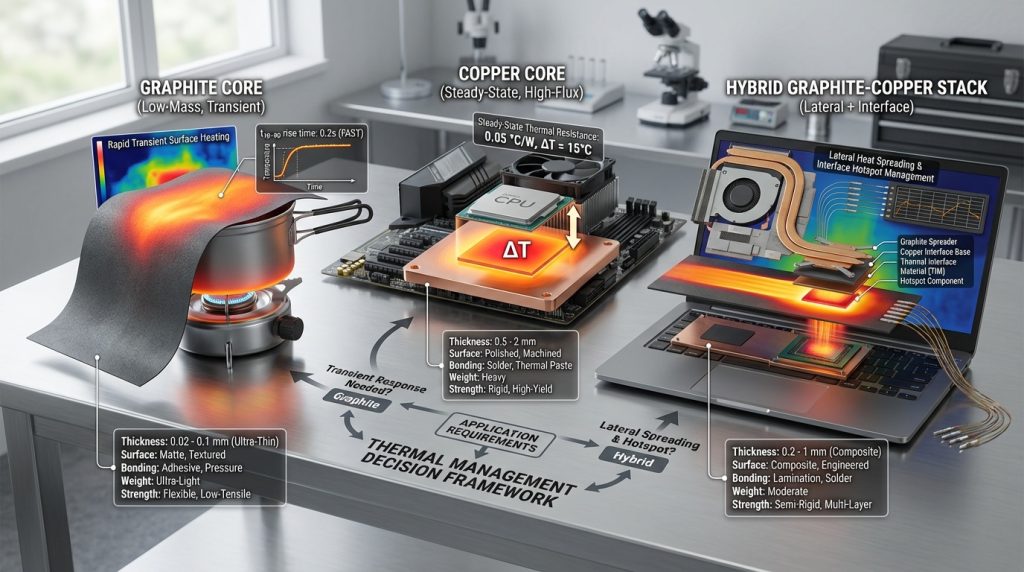

Choosing the Right Core: A Practical Decision Framework for Your Use Case

Use this checklist and quick decision flow to pick graphite, copper, or a hybrid—and to design validation tests for your specific geometry and loading.

Rank priorities (quick flow)

Material recommendations + validation tests

Implementation notes (practical specs)

With this framework you can narrow candidates, set targeted tests, and prototype hybrids quickly before final specification—next, the article wraps up with a concise summary of which core fits which need.

Summary: Which Core Gives Faster Heat Response for Your Needs?

In most bulk, high-mass applications you’ll get faster transient heating and cooling with copper because its higher thermal diffusivity moves heat more quickly through the material. Graphite, however, can outperform copper when mass is low, heat spreading is directional, or weight and form-factor constraints dominate—especially in thin laminates, heat pipes, or anisotropic spreads.

Choose based on your priorities and geometry, then validate with representative transient tests under real boundary conditions. Use the decision framework and measurement guidance in this article to select and verify the best core for your application.